“…India won. No, Pakistan won! I’m like, “No, dude, the British won.” -Hasan Minhaj, Comedian, on Indian Elections.

In the midst of the staunch rivalry that exists between the South Asian states, it is easy to forget that there exists a shared history of brutality, of colonial plunder, of manufactured division among them. But the wound is still there. It has always been there. And without confronting it or healing it, the states have rather tried to exploit those wounds to sow the seeds of hatred. This sublimation of actual pain hasn’t helped the South Asians, rather hindered their development. Despite being a region with immense potential, it remains busy with quarrels. This is what the comedy skit of Hasan Minhaj tried to deliver through humour: as the South Asians remain divided among themselves through war and aggression, the actual winner is the British, or the West in general.

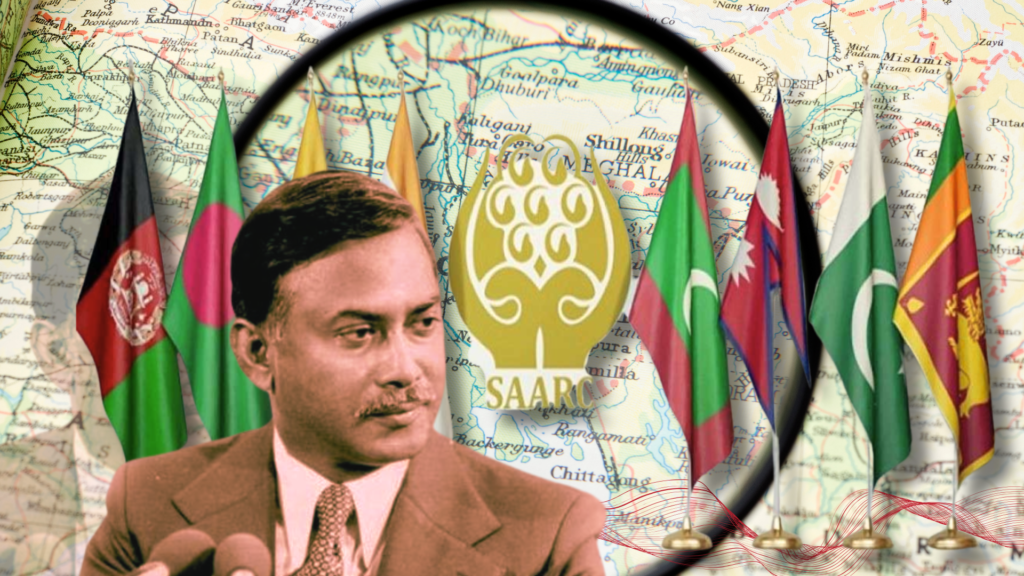

Maybe this was the realisation that led the late President Ziaur Rahman to formally pursue the establishment of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation, or SAARC, in short. SAARC was supposed to be an alliance for social, cultural and economic exchange among its member states, which included Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, the Maldives, Nepal, and Bhutan in the beginning, with Afghanistan joining in 2007. Collectively, the total population of SAARC is currently at least 1.9 billion, with its diverse geography ranging from deserts to river basins and archipelagos. With such a resource-rich environment, SAARC could have turned South Asia into an economic and cultural powerhouse.

Yet, it didn’t.

SAARC is considered to be one of the least effective regional cooperatives among those that exist currently. As Shadique Mahbub Islam writes, “The intraregional trade is barely 5% of the region’s total trade. In comparison, the intra-regional trade share is about 60% of the total trade in Europe, 50% in East Asia and the Pacific, 22% in Sub-Saharan Africa, 25% in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).” (From Saarc to Bimstec: The failure of regional cooperation in South Asia, 23 March 2025). However, the Chief Advisor of the Government of Bangladesh, Dr Muhammad Yunus, has hinted at the prospect of reviving the SAARC during his tenure, which elicited mixed reactions from India and Pakistan, who are responsible for the current stalemate situation of SAARC.

SAARC was supposed to be a platform for the South Asian states to cooperate, the states which have been the victims of colonial plunder and humiliation. But in the end, it became a battleground for hegemony between two nuclear powers – India and Pakistan. The antagonism between India and Pakistan has long exerted too much influence on South Asian geopolitics, with the other countries being forced to act as bystanders. The regional balance is heavily tilted towards India, due to it being the largest country in terms of area and population. In fact, the SAARC meeting that was supposed to occur in 2016 was boycotted by India, and it was followed by other members, such as Bangladesh and Afghanistan. There has been no summit since then. The situation has only gotten worse since the Taliban regime came into power, as India and Afghanistan have united against Pakistan.

It is important to note that even though SAARC was supposed to act as the platform for regional cooperation, the SAARC never actually focused on bilateral issues, and it seems the official charter avoids mentioning such problems, unintentionally or not. These have had far-reaching consequences. The prime example of such a case is the Kashmir dispute. This has remained unsolved in the last 79 years, which has only worsened the life of Kashmiris on either side of the fence. Another example would be the dispute over transboundary rivers, which have cursed the lives of thousands of people in the North Bengal of Bangladesh.

This is one of the major flaws in the operations of SAARC – it doesn’t seek to reconcile the historical errors which have been made to South Asia by Western colonial powers and facilitated by the wrong decisions of previous leaders. If SAARC is to be revived at all, it must include a reform in its charter which addresses the bilateral disputes. Otherwise, these contentious issues will never see the light of diplomatic solutions. Rather, they would continue to be populist talking points of the political parties in those respective countries.

Another modification must be done to recognise human rights as inviolable in the organogram of the organisation. Similar to the EU Charter, there must be a new document that would legally bind the member states to honour human rights. Human rights violations are a common occurrence in different parts of South Asia; again, the Kashmiris are an example, although they are not the only ones. Pakistan has also been accused of human rights violations, especially in Balochistan, as well as in Bangladesh. A SAARC revival would be meaningless if the constituents of the cooperation cannot be ensured with basic human rights.

Modification must also be done in how the decisions are processed. The requirement for unanimous agreement from all member states largely impedes decision-making, as political distrust among countries can lead them to have differing opinions, and the process goes nowhere. This requirement for unanimity turns the smaller countries, such as Bhutan, Nepal or Bangladesh as mere spectators in the game where two superpowers are controlling the show. This process needs to be changed if the SAARC is to be revived effectively. Otherwise, the India-Pakistan rivalry would continue to hinder the progress of SAARC for an indefinite time.

It must be said that an effective SAARC would definitely facilitate the whole South Asian region. Only a cooperative and harmonious process can ease the different ethno-religious tensions and war over resources in this region, and Ziaur Rahman must be praised for thinking far ahead of his time in taking the initiative to build such an organisation. Bangladesh should take the lead to revive the SAARC for its own sake, with further modifications to make that revival actually effective in solving issues, not just in abstract, but also through concrete means. In the world of chronic injustices, South Asia can become an example of how regional cooperation can facilitate and ensure a better life for everyone involved. Only this would be truly honouring the late President Ziaur Rahman. We certainly hope that the elected government that comes next in February 2026 attempts to revive an effective SAARC.

Sadman Ahmed Siam is an independent columnist and a student at the Islamic University of Technology.