On 12 February 2026, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party won 209 of 297 declared seats in the most significant election since the country’s return to competitive democracy. The Jamaat-led 11 Party Alliance secured 77. The headline story is a BNP landslide. But the more revealing story lies in the map — specifically, in who voted for whom, where, and who did not vote at all.

This piece draws on a district-wise statistical analysis of all 64 districts, correlating the Election Commission’s unofficial results with socio-demographic indicators from the BBS Census 2022, the Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES) 2022, the Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS) 2022, the Labour Force Survey 2022, and madrasa enrolment data from BANBEIS 2023. Multiple statistical tests — correlation analyses with multiple-comparison corrections, regression models, and group comparisons — were used to identify which demographic variables genuinely distinguish the two parties’ voter bases and which popular assumptions do not survive contact with data.

The findings challenge several common narratives. They also raise a question that Bangladesh’s new parliament will eventually have to confront: what does it mean when a party’s electoral geography so closely mirrors the map of one of the country’s most stubborn social crises?

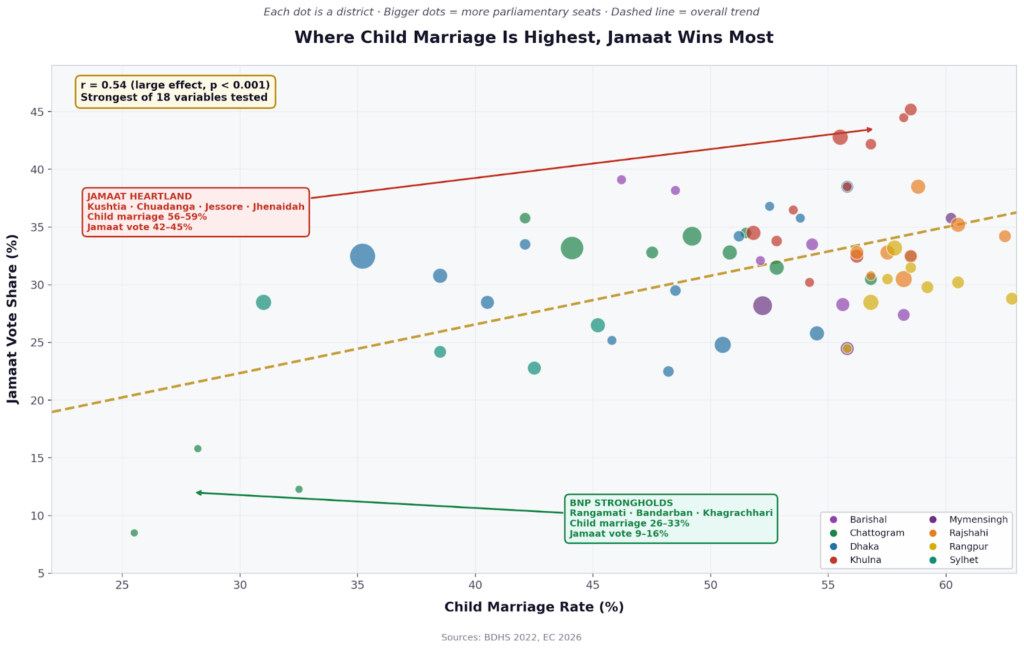

Child marriage: The strongest signal in the data

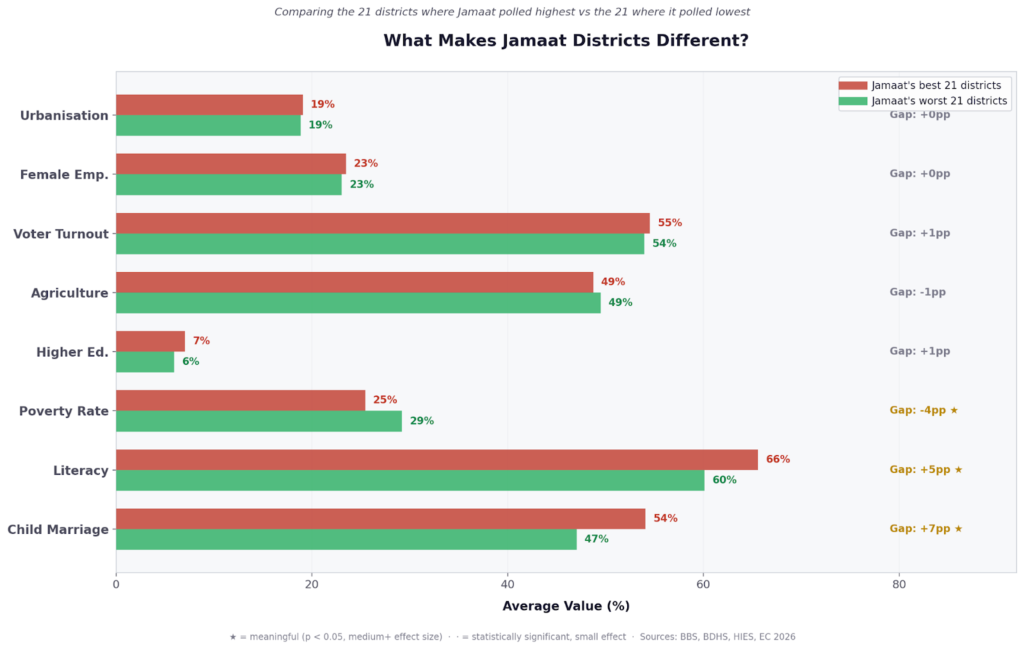

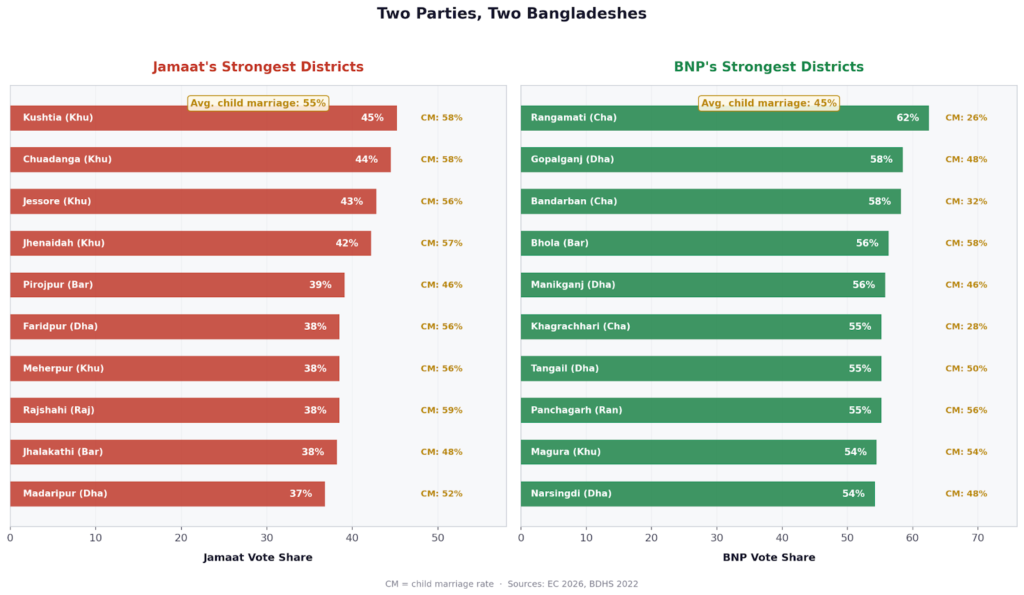

Among the 18 socio-demographic variables tested against both parties’ district-level vote shares, child marriage prevalence emerged with the strongest statistical association with Jamaat’s performance — highly significant even after correcting for multiple comparisons. It was stronger than poverty, literacy, urbanisation, madrasa density, or any employment variable.

The pattern is visible on the map. In Kushtia, where Jamaat swept three of four seats, child marriage stands at 59 per cent. Chuadanga, where the party won every seat: 57 per cent. Jessore (five of six seats): 56 per cent. Jhenaidah, Satkhira, Meherpur — the same pattern holds across Khulna division and parts of Rajshahi.

Conversely, BNP’s largest margins came from districts at the other end of this spectrum. The Chittagong Hill Tracts — Rangamati, Bandarban, Khagrachhari — have child marriage rates between 25 and 33 per cent. Dhaka, at 35 per cent, delivered overwhelming BNP majorities. Sylhet and Chittagong city, both BNP strongholds, sit below the national average. For BNP, the association runs in the opposite direction — statistically significant and negative.

A word of caution is essential here. This is a district-level correlation, not a statement about individual voters. It would be an ecological fallacy — the most basic error in aggregate-level analysis — to conclude that people who support child marriage vote Jamaat. The same geographic logic that explains this correlation could partially explain it away: Jamaat’s organisational strength is concentrated in the southwest, and the southwest happens to have higher child marriage rates. The two phenomena may share underlying causes — patriarchal norms, limited secondary schooling for girls, dowry economics, restricted female agency — without one causing the other.

The same epistemic humility applies to BNP. Several variables that look unflattering for the party — a negative association with literacy, for instance — are geographic artefacts. BNP ran up its largest margins in the Hill Tracts and the Rangpur-Mymensingh belt, regions with the country’s lowest literacy rates (48 to 56 per cent). This says nothing about the education levels of individual BNP voters. Neither party should be caricatured by the aggregate characteristics of the districts it won.

Still, after those caveats, the child marriage correlation remains the single strongest demographic signal in the dataset. It persists in multiple regression models even after controlling for other variables. And it sits within a cluster of related findings — weaker associations with female labour force participation, higher education access, and measures of traditional gender norms — that together point toward a meaningful dimension of the electoral divide.

Where the votes went: A geography of organisational depth

The most powerful predictor of where Jamaat won is not any socioeconomic variable — it is geography itself. Khulna division accounts for 25 of the party’s 68 independently won seats. Add Rangpur (16 seats) and parts of Rajshahi (11 seats), and the western-northwestern belt accounts for the vast majority of Jamaat’s parliamentary strength. In the east — Chittagong, Sylhet, Mymensingh — the party’s showing was, as The Business Standard put it, “disappointing.”

What explains this geographic concentration? The data alone cannot fully answer the question, but several contextual factors converge.

Prothom Alo’s post-election analysis noted that political analyst Mahbubul Alam identified three pillars of Jamaat’s rise: grassroots organisational rebuilding after 2010 during the party’s years in the political wilderness, a digital-first campaign that reached first-time voters effectively, and years of charitable networks in rural and semi-urban areas. These investments were concentrated in the southwest and northwest.

A deeper structural explanation comes from Netra News. Their post-election analysis observed that across Khulna and parts of Rajshahi, the Rapid Action Battalion dismantled armed leftist groups during the 2001–2006 BNP government. In Rangpur, the Jatiya Party began to decline after the death of Hussain Muhammad Ershad. In both regions, as local power structures weakened — whether through the collapse of leftist armed groups or the decline of the Jatiya Party — Jamaat gradually moved in to fill the organisational vacuum. This is not the story of a sudden ideological conversion; it is the story of a disciplined political party occupying space that other forces abandoned or were forced out of.

The Awami League’s fifteen-year authoritarian rule (2009–2024) compounded this dynamic. By banning Jamaat from elections in 2013, the Hasina government inadvertently allowed the party to rebuild its cadre base without the compromises and corruption of governance. BNP Secretary General Mirza Fakhrul Islam Alamgir was characteristically blunt after the 2026 results: “Whenever democracy is suppressed and people’s voices are stifled, extremist forces begin to emerge — that is what has happened here.”

Three islams, two electorates: Understanding the religious ecology

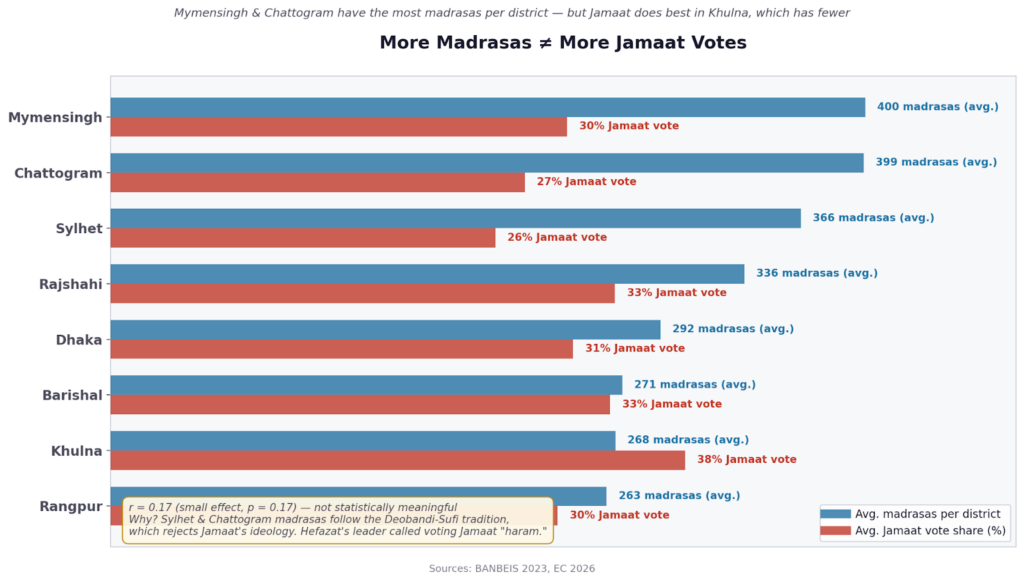

The geographic divide acquires deeper meaning when placed alongside Bangladesh’s internal religious landscape — a dimension rarely discussed in electoral analysis but powerfully evident in the results.

Bangladesh’s Islamic political space is broadly divided into three doctrinal streams. Prothom Alo, in a July 2025 analysis of Islamic party unity efforts, described them as: the “reformist” stream led by Jamaat-e-Islami, based on Maududi’s political-Islamic philosophy; the Deobandi stream, rooted in Qawmi madrasas, represented by parties like Islami Andolan Bangladesh and the non-political Hefazat-e-Islam; and a third, smaller Barelvi/Razavi current. These three streams have never successfully united in an electoral alliance. The doctrinal distance between them — particularly between Jamaat and the Deobandi establishment — is not a minor footnote. It is a defining fault line of Bangladeshi religious politics.

The Deobandi-Qawmi tradition, which dominates eastern Bangladesh, upholds taqlid — strict adherence to the Hanafi school of Islamic jurisprudence. Its scholars follow a traditional scholarly authority structure centred on the great madrasas: Hathazari in Chittagong (founded 1901, the preeminent Qawmi institution in Bangladesh), the seminaries of Sylhet, the mosques and khanqahs of the old scholarly networks. While Deobandi theology is itself reformist in origin, it has in Bangladesh accommodated and coexisted with local Sufi shrine traditions. Sylhet — home to the shrine of the 14th-century Sufi saint Hazrat Shah Jalal, the country’s most visited religious site, and approximately 360 other mazars — is simultaneously one of the most Qawmi-dense and most Sufi-influenced regions in the country. Chittagong hosts the shrine of Shah Amanat. These are regions where spirituality and scholarly authority intertwine.

Jamaat’s intellectual tradition is fundamentally different. It follows Maududi, who rejected taqlid and instead advocated for ijtihad (independent reasoning) in the service of building an Islamic political state. The Deobandi scholars view this as theologically dangerous. As Muslim Mirror reported, the Hefazat leadership considers “the Maududian creed to be wrong,” accusing Jamaat of criticising the Sahaba (the Prophet’s companions) and promoting a version of Islam incompatible with traditional Sunni orthodoxy. Hefazat Ameer Babunagari’s pre-election declaration that voting for Jamaat was “haram” was not a one-off remark — BDDigest compiled a catalogue of his statements spanning over a year, in which he repeatedly described Jamaat as “more harmful than Qadianis” and warned that if Jamaat came to power, it would shut down Deobandi madrasas.

The depth of this hostility matters electorally. Hefazat’s Babunagari explicitly supported BNP candidates in Chittagong. BNP also maintained its longstanding alliance with Bangladesh Jamiat Ulama-e-Islam, a Qawmi clerical party that — significantly — supported the 1971 liberation struggle, giving BNP a way to court the Qawmi vote without the ideological baggage of Jamaat’s wartime history. The result: in Sylhet and Chittagong, despite having some of the highest Qawmi madrasa densities in the country, Jamaat’s vote share remained well below its national average. Madrasa density alone does not significantly predict Jamaat’s vote — what matters is the kind of Islamic tradition those madrasas represent.

Now consider Jamaat’s western strongholds. The religious ecology of Rajshahi and its surroundings is markedly different. This region is the historic centre of the Ahle Hadith movement in Bangladesh — the South Asian variant of Salafism. The two movements are ideologically distinct: Jamaat follows Maududi; the Ahle Hadith trace their lineage through Shah Waliullah and Ibn Taymiyya. They are organisationally separate and have at times been rivals. But they share characteristics that set them apart from the Deobandi-Qawmi mainstream. Both reject taqlid. Both oppose the Sufi shrine culture that defines eastern Bangladesh’s religious practice — viewing mazar devotion as bid’ah (innovation) at best, shirk (idolatry) at worst. Both prioritise scripturalist reform over traditional scholarly authority. Both have drawn from transnational networks — Jamaat from the Muslim Brotherhood tradition, the Ahle Hadith from Saudi-influenced Wahhabi channels. And both operate as modern social movements rather than through the hierarchical teacher-student authority (silsila) that structures Qawmi life.

An academic thesis based on fieldwork in Rajshahi described the region as “the scene of a religious contest between the self-described Hanafis, who include various expressions of Islamic faith and practice, and Salafi reformist groups known as Ahl-i-Hadith” who “actively seek to purify local Islam.” The Middle East Institute similarly noted that in Bangladesh, political Salafists “fail to gather the popular support necessary to achieve independent political influence” — but the religious environment they helped create, one more receptive to scripturalist reform and less anchored in shrine-based devotion, may have made the soil more fertile for Jamaat’s distinct but directionally similar message.

This is not an argument that Jamaat and Ahle Hadith are the same — they are not, and conflating them would be both analytically wrong and unfair. It is an observation that the religious environments of eastern and western Bangladesh differ in ways that shape political receptivity. The Sufi-Qawmi ecosystem of the east, with its deep roots in devotional practice and traditional scholarly authority, resists Jamaat. The more reform-oriented, scripturally focused landscape of the west is more hospitable to it. The statistical finding that madrasa density does not predict Jamaat’s vote, while geography powerfully does, is consistent with this interpretation.

The women’s vote: More complicated than either side admits

Jamaat’s public discourse on women’s roles triggered sharp criticism during the campaign. Several party leaders made statements questioning women’s participation in certain sectors of the workforce — remarks that provoked backlash from urban professional women, women’s rights organisations, and the liberal educated class. The Atlantic Council’s post-election analysis noted that “the prospective influence of Islamist actors in the Jamaat-e-Islami coalition prompted reflection among segments of the electorate — particularly some women — regarding the social and policy direction of governance.”

The district-level data shows a weak negative association between female labour force participation and Jamaat’s vote share, while BNP’s trends mildly positive — small effects, but directionally consistent with the narrative that working women leaned away from Jamaat.

However, honesty demands acknowledging a finding that complicates this picture. Netra News conducted an analysis of more than 1,600 single-sex polling stations outside Dhaka and found that in the centres Jamaat carried, female-only stations outnumbered male-only ones, while BNP’s ratio skewed more male, at roughly 6:4. Their assessment: “A new cohort of socially conservative women — often visibly religious — appears to be finding a sense of belonging and community in Jamaat’s message.”

This is an important corrective. The women’s vote was not monolithic. Urban professional women may have leaned BNP or abstained; a different segment of conservative, religiously observant women appears to have actively chosen Jamaat. The child marriage correlation, read in this light, does not simply reflect male patriarchal preferences being imposed on passive communities — it may also reflect the preferences of women who inhabit those communities and subscribe to their social norms. This is uncomfortable for both liberal and Islamist narratives, and it deserves further investigation through individual-level survey data rather than district-level inference.

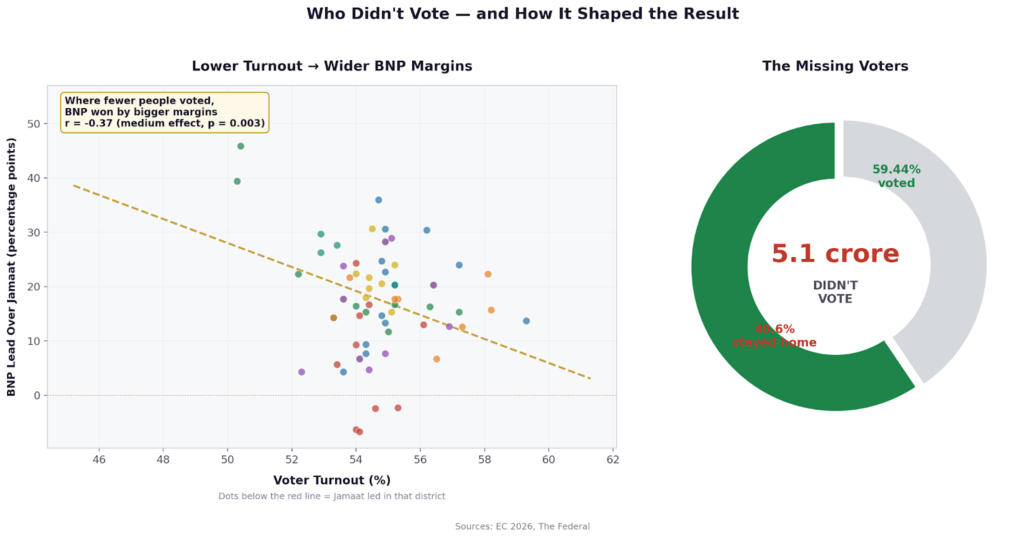

The ghost at the feast: Fifty-one million missing voters

No analysis of this election is complete without reckoning with who did not participate. Official turnout was 59.44 per cent. Over 51 million registered voters stayed home.

The Awami League’s “No Boat, No Vote” campaign — referencing the party’s iconic nouka symbol being absent from the ballot — explicitly called for a boycott. The party, banned under the Anti-Terrorism Act following the July Revolution and the International Crimes Tribunal proceedings against Sheikh Hasina, rejected the election as illegitimate. An Awami League spokesperson told The Federal that “people have largely stayed away from the polls because they want us back,” claiming the party “even in the worst of situations, is known to command a 40 per cent loyal vote bank.”

The statistical data offers a suggestive, though not definitive, clue. Turnout shows a statistically significant negative association with BNP’s vote share. In districts where fewer people voted, BNP tended to win by wider margins. This is consistent with a scenario where Awami League-leaning voters — particularly the urban liberal and secular-leaning professional class that formed AL’s core — disproportionately abstained, amplifying BNP’s margins without the party needing to expand its actual base.

Dhaka tells the story most clearly. The Daily Star reported midday turnout figures of 27 to 29 per cent in several Dhaka constituencies — among the lowest in the country. In a city with millions of registered voters, this represents a vast reservoir of uncast ballots.

But the turnout story has another dimension that complicates the neat narrative. Netra News reported that some Awami League supporters with a history of party activism appear to have voted for Jamaat, not BNP. Their logic was pragmatic: they feared a harsher crackdown under BNP, whose local activists had initiated thousands of criminal cases against AL members, whereas Jamaat struck a comparatively softer tone. If true, this means the AL voter absence did not benefit both parties equally — BNP gained from abstention, but Jamaat may have gained from defection.

The demographic profile of the missing voters matters enormously for interpreting the data. The liberal-secular-urban demographic that historically supported the Awami League — and that would likely have complicated both parties’ statistical profiles — is largely invisible in the results. The BNP-Jamaat demographic divide captured in this analysis is, in part, shaped by whose voices were present and whose were absent. A future election with the Awami League or a successor secular party on the ballot would almost certainly produce a different demographic map.

What the data does not show

Transparency requires stating what the analysis does not find.

Several variables showed no statistically significant association with either party’s vote share: industrial employment, service sector employment, and population density among them. The poverty-Jamaat relationship, while statistically significant (Jamaat performs better in less poor districts), is moderate and does not survive as strongly in multivariate models. The “Jamaat is a party of the poor” narrative is not supported; but neither is “Jamaat is a party of the rich.” Its base is economically middling — smallholder agriculture, market towns, remittance income.

The multiple regression model — which tests all variables simultaneously — explains only a moderate share of the variance in either party’s vote. Demography is not destiny. Candidate quality, local organisational depth, patronage networks, campaign strategy, and the specific dynamics of the July Revolution and its aftermath all matter enormously, and none of them appear in a dataset. As Professor AKM Waresul Karim of North South University told Prothom Alo, Jamaat successfully repositioned itself from a conservative right-wing identity towards the centre-right — a strategic choice that statistical variables cannot capture.

What this means for Bangladesh

The data paints a picture of two overlapping but distinct Bangladeshes.

BNP’s Bangladesh is geographically sprawling, socioeconomically diverse, and religiously plural. Its voters span Sufi devotees and Qawmi scholars in the east, secular professionals in Dhaka, indigenous communities in the Hill Tracts, and rural labourers in the northwest. It is a coalition held together not by ideological purity but by a broadly centrist political identity — one that, at its best, can accommodate difference. Netra News described it well: “Socially liberal voters, parts of the left, seculars, minority Hindu communities and even indigenous voters in the Chittagong Hill Tracts lined up behind a party they are not usually associated with.”

Jamaat’s Bangladesh is geographically concentrated, organisationally disciplined, and socially conservative in character, though increasingly diverse at the margins through the NCP’s urban youth base. Its heartland is a zone of higher child marriage, lower female workforce participation, reform-oriented religious ecosystems, and a political culture responsive to moral governance messaging. It is a genuine electoral force — the party’s leap to 68 seats and over 30 per cent of the popular vote is historically unprecedented — but it is regionally bounded in ways that the party’s social media presence may obscure.

The challenge for BNP is that its coalition is broad but potentially fragile. Liberals, Qawmi scholars, minorities, and rural networks do not all want the same things. If the new government mistakes a two-thirds majority for a blank cheque, it may discover that the quiet coalition which delivered victory can unravel quietly.

The challenge for Jamaat is different. The child marriage correlation, whatever its causal mechanism, points to a voter base concentrated in districts where girls’ education, women’s economic participation, and gender equity lag behind the national average. If the party is serious about its stated pivot toward the centre-right, it will need to demonstrate — through governance in its opposition role, through its charitable networks, through its educational institutions — that its model can improve outcomes for women and girls, not merely accommodate existing norms. A party’s electoral geography is not its destiny, but it is its starting point.

For civil society, the overlap between child marriage prevalence and a specific political geography is a call to invest in precisely those districts — Kushtia, Jessore, Chuadanga, Rajshahi, Satkhira — where patriarchal norms remain most entrenched. These interventions are not partisan; they are developmental. But they have political implications, because the social conditions that sustain conservative political movements are the same conditions that development programmes aim to change.

And for all of us: an election where 51 million voters had no meaningful choice on the ballot is an incomplete expression of democratic will, regardless of how orderly the process was. The reintegration of the political mainstream — through accountability, legal process, and eventual reform rather than permanent exclusion — is not a favour to the Awami League. It is a necessity for any future election to fully represent the country.

Conclusion

Numbers do not choose sides. But they can tell us where to look, and sometimes what we find is uncomfortable for everyone. The child marriage correlation is uncomfortable for Jamaat. The turnout gap is uncomfortable for those who would claim this election as a full democratic renewal. The Hefazat-Jamaat split is uncomfortable for anyone who imagines Bangladesh’s religious landscape as a monolith. The Netra News finding on women voters is uncomfortable for the liberal assumption that women uniformly rejected Jamaat. And BNP’s dependence on absent AL voters is uncomfortable for a party that needs to build durable support, not merely inherit a vacuum.

What the data ultimately reveals is an election shaped as much by who did not vote as by who did, and a country where the sharpest dividing lines run not between rich and poor, or literate and illiterate, but between different religious ecologies, different experiences of social change, and different answers to the question of what role faith, gender, and tradition should play in public life.

That question is not just demographic. It is political. And the ballot box, whether we like it or not, has already begun to answer it.

Methodology Note: This analysis is based on a dataset of 64 districts covering 299 constituencies, using EC unofficial results (via BSS, ekhon.tv, and the Daily Star), BBS Census 2022, HIES 2022, BDHS 2022, BBS SVRS 2023, LFS 2022, BANBEIS 2023, and UNICEF/Girls Not Brides division-level child marriage data. Statistical tests include Pearson and Spearman correlations with Bonferroni and Benjamini-Hochberg corrections, OLS and logistic regression with VIF diagnostics, chi-square tests, Mann-Whitney U tests, and Shapiro-Wilk normality assessments. Alliance-level vote shares for NCP and Khelafat Majlis are estimated from national proportions scaled by urbanisation and madrasa density respectively. Full dataset and statistical output available from the author upon request.

Dr. Md Marufur Rahman is a physician, public policy analyst and healthcare researcher. His academic and work interests are: health systems research, action-outcome mapping, performance management, predictive modeling, data driven decision and feature clustering.

References:

- Bangladesh Election Commission, 13th National Parliamentary Election Unofficial Results, February 2026.

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Population and Housing Census 2022; Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES) 2022; Labour Force Survey (LFS) 2022; Sample Vital Registration System (SVRS) 2023.

- National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS) 2022.

- Bangladesh Bureau of Educational Information and Statistics (BANBEIS), Bangladesh Education Statistics 2023.

- UNICEF/Girls Not Brides, Child Marriage in Bangladesh: Division-Level Estimates.

- Prothom Alo, “Jamaat’s major surge, highest-ever vote haul,” February 2026. https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/politics/2m494oaaa8

- The Business Standard, “Jamaat feat in 13th national polls historic too: Analysts,” February 2026. https://www.tbsnews.net/bangladesh-election-2026/jamaat-feat-13th-national-polls-historic-too-analysts-1361141

- Netra News, “Why the BNP won — and what could yet undermine it,” 16 February 2026. https://netra.news/2026/bnp-victory-bangladesh-election/

- Atlantic Council, “What Bangladesh’s first post-Hasina election means for the country’s future,” 13 February 2026. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/dispatches/what-bangladeshs-first-post-hasina-election-means-for-the-countrys-future/

- The Daily Star, “Voting for Jamaat ‘not permissible’ for Muslims: Hefazat chief,” February 2026. https://www.thedailystar.net/news/national-election-2026/news/voting-jamaat-not-permissible-muslims-hefazat-chief-4099716

- The Business Standard, “Voting for Jamaat ‘haram’, says Hefazat ameer,” February 2026. https://www.tbsnews.net/bangladesh-election-2026/voting-jamaat-haram-says-hefazat-ameer-1353846

- Muslim Mirror, “Why does Hefazat-e-Islam not support Jamaat-e-Islami in Bangladesh?” October 2025. https://muslimmirror.com/why-does-hefazat-e-islam-not-support-jamaat-e-islami-in-bangladesh/

- BDDigest, “Hefazat Ameer’s bold statement about Jamaat-e-Islami,” September 2025. https://en.bddigest.com/hefazat-ameers-bold-statement-about-jamaat-e-islami/

- Prothom Alo, “Will Islamic forces form an electoral unity, what will happen if they do?” July 2025. https://en.prothomalo.com/opinion/op-ed/evrrvsmfkk

- Prothom Alo, “BNP moves to woo Hefazat-e-Islam,” September 2025. https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/politics/mvhtpdos2b

- Middle East Institute, “Trajectories of Political Salafism: Insights from the Ahle Hadith Movement in Pakistan and Bangladesh.” https://www.mei.edu/publications/trajectories-political-salafism-insights-ahle-hadith-movement-pakistan-and-bangladesh

- International Islamic University, Islamabad, “Ahl-e-Hadith Movement in Bangladesh: History, Religion, Politics and Militancy.” https://www.iiu.edu.pk/wp-content/uploads/downloads/ird/downloads/Ahl-e-Hadith-Movement-in-Bangladesh-Complete.pdf

- ORF, “Political Salafism in South Asia,” December 2024. https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/political-salafism-in-south-asia

- Dhaka Tribune, “What is the Ahl-e Hadith movement?” March 2018. https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/140252/what-is-the-ahl-e-hadith-movement

- “Lived Islam in Bangladesh: Contemporary religious discourse between Ahl-i-Hadith, ‘Hanafis’ and authoritative texts, with special reference to al-barzakh” (PhD Thesis, Rajshahi fieldwork). Academia.edu.

- New Age, “Beyond Fear: Sufism and shrines of Sylhet.” https://www.newagebd.net/post/opinion/257224/beyond-fear-sufism-and-shrines-of-sylhet

- Wikipedia, “Deobandi movement.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deobandi_movement

- Banglapedia, “Mazar” and “Ahl-e-Hadith.” https://en.banglapedia.org/

- The Federal, “Bangladesh poll body claims 55-60% turnout, but ground reports tell a different story,” 12 February 2026. https://thefederal.com/category/international/bangladesh-elections-2026-turnout-bnp-jamaat-muhammad-yunus-229606

- Outlook India, “Bangladesh Elections 2026: Awami League Missing For First Time In 3 Decades,” February 2026. https://www.outlookindia.com/international/bangladesh-elections-2026-awami-league-missing-for-first-time-in-3-decades

- ACLED, “Bangladesh heads toward a landmark election amid rising political violence,” February 2026. https://acleddata.com/report/bangladesh-heads-toward-landmark-election-amid-rising-political-violence

- Mukti Potro, “What explains the rise of Jamaat-e-Islami in Bangladesh’s western frontier?” 15 February 2026. https://muktipotro.com/7212

- Majumder, Mohammad & Ahmed (2019), “Socio-Spiritual and Economic Practices of Mazar (Holy Shrines) in Sylhet,” International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Studies.

- Bangladesh Journal of Arts, Sciences, Business and Humanities, “Understanding the Qawmi Madrasah System in Bangladesh and Its Educational Framework,” Vol. 70(1), June 2025.